Who are we?

We are three New Yorkers who are interested in integrating the technology and wealth of knowledge that already exists in our city for climate resiliency. As students at the CUNY Graduate Center’s department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, our research is forward-thinking and service-oriented, with the goal of preparing and protecting our city’s most vulnerable inhabitants from climate change. Our interdisciplinary expertise includes: climate science, hydrology, restoration ecology, local stewardship, and nature-based solutions, making our team uniquely suited to approach flood solutions at the Brooklyn Navy Yard with a multi-faceted approach. Our specific concern is flooding, and with 72% impervious cover and 520 miles of shoreline, New York City is especially vulnerable to flooding from precipitation (pluvial) and storm surges (coastal). New Yorkers are resilient, and the solutions are out there, our goal is to bring them together so we can all learn to live with water.

Who are you?

You are anyone, but hopefully someone who cares about the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a place to grow, thrive, and share. The Brooklyn Navy Yard has a fascinating history as it has transformed from a salt marsh to a ship building site to a business hub through the last few centuries. Between the bike lanes, public housing, event venues, the Naval Cemetery, the businesses, and more, the Brooklyn Navy Yard has something to offer everyone, and we created a concept for a dashboard as a way for everyone to offer something back. Read on to learn about the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s history, current challenges, and to view the potential dashboard’s components. The dashboard is meant to serve as a dynamic interface for the city to input real solutions and view real time data as well as provide a platform for community input and imagining.

Contents:

Dashboard Concept:

Given everything we observed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, we propose a concept for a neighborhood-specific urban water dashboard that integrates data from a proposed blue-green infrastructure installation.

The conceptual dashboard could include:

- Integration of Existing Resources

- Nearby Floodnet Sensors

- MyCoast app

- Links to the Brooklyn Grange’s website

2. Given the proposed installation of a blue-green infrastructure project (like the proposed changes to the Wegman’s Parking lot), the dashboard could include real time sensor data from:

- Water flow

- Soil moisture

- Soil salinity

- Surface temperature (from soil and pavement)

3. Opportunities to Share:

- A form to submit comments and geo-located photos of flooding and other concerns

- Historical information, links to resources, in an open-ended story-telling format that would invite contributors to add details or sections

This is a non-exhaustive, conceptual list, and we welcome all suggestions to facilitate a deeper understanding of the space, provide education and outreach opportunities.

Historical Context of Land Use in the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Originally a salt marsh in a highly (biologically) productive estuary, much of the Brooklyn Navy Yard (BNY) as we know it today is a human construct. To understand the unique flood risks of this area as well as the current landscape and ability for the public to access the space we explain selected parts of this area’s transformation since early colonization began. A timeline from Brooklyn Navy Yard can be found here.

Early Colonization Land Use Changes:

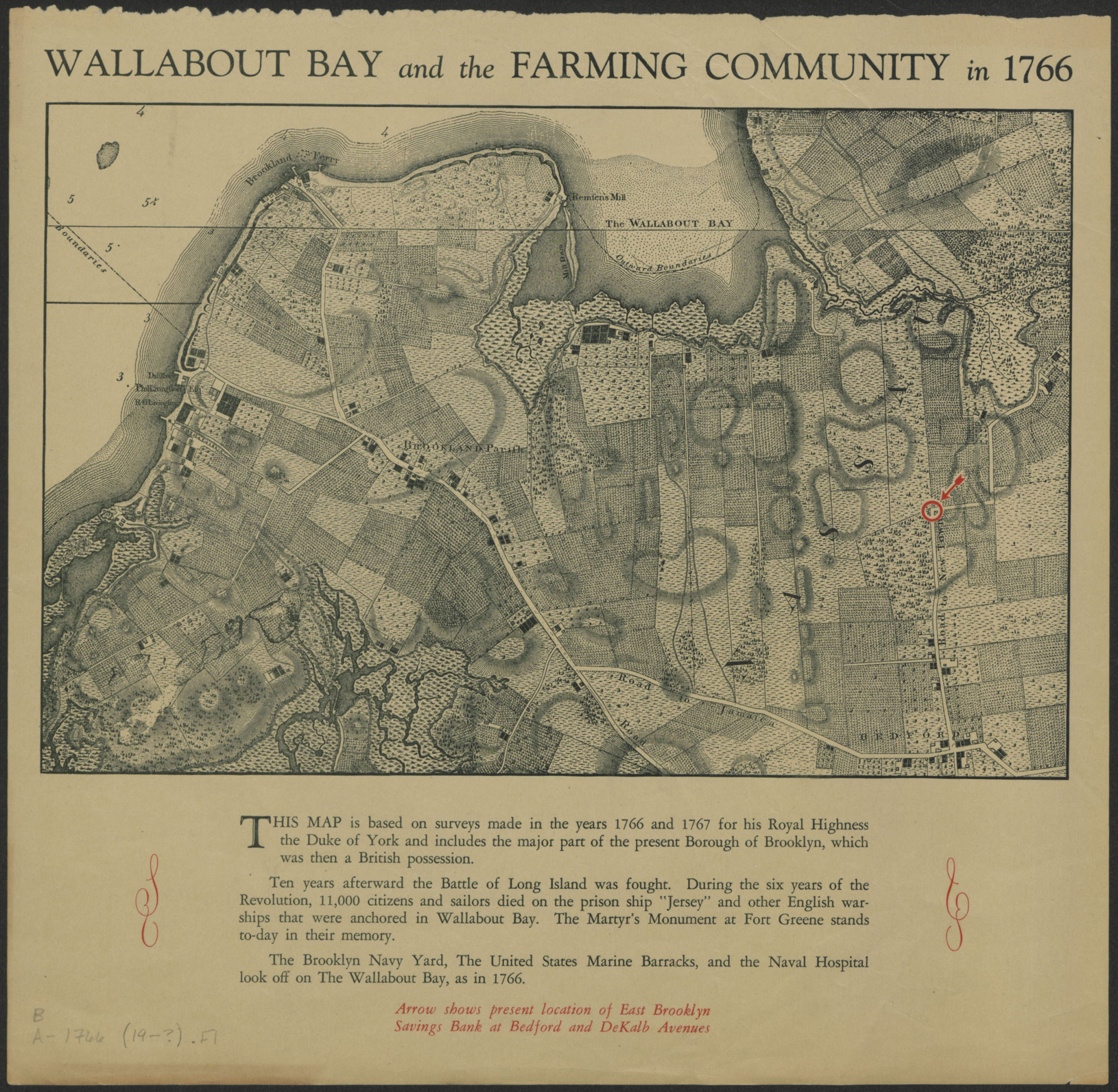

The salt marshes seen in the top left rendering were first modified by farming and the building of dams to create tide driven mills by the Dutch in the late 1600s, which are represented in the map below. The land was purchased from the Lenape in 1637 by one Dutch family. It was named Wallabout bay, and some people still refer to the neighborhood as Wallabout. During the American Revolutionary War, English prison ships and warships were stationed in the bay. The bay’s use evolved into a ship building site, with President John Adams establishing the site in 1801 and the first building being built in 1806.

Land Use Changes in the Military Industrial Era

By the era of 1939-1945, the BNY employed a staggering 70,000 employees who built warships and commercial ships. The NYCHA housing surrounding the Brooklyn Navy yard- specifically, the Farragut, Ingersoll, and Whitman houses were built in 1944 to “address the pressing housing needs of the thousands of employees at the nearby Brooklyn Navy Yard”. (Nelligan White) The land that the houses are built upon, as well as the bordering Commodore Barry park, have lots of lawn space, which likely help absorb more rainwater than the streets and other built up areas around it. The NYCHA housing complexes are generally in dis-repair and in need of investment. See the below map for the extent of the housing complexes and the park, which surround the southern edge of the BNY.

The military-run industrial ship building industry at the BNY closed officially in 1966. The City gained control of the yard in the same year and created a non-profit to run the space. Some commercial ship building companies remained operating, albeit in a smaller scale. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation (BNYDC) was established in 1981 (the second non-profit to be set up) and is still managing the space to this day. As the economic contraction of the ship-building industry progressed, the BNYDC sought other tenants and created several programs to encourage businesses to set up.

Presently, there are 500 small businesses operating in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, with a high concentration of green or climate related businesses. As these businesses thrived, more investment was made in the area- over 700 million dollars of development was in process by 2017. However, the remains difficult to access by public transportation.

Contemporary Land Use and Stakeholders

Prior to the creation of a NYC ferry stop in 2019, the BNY was inaccessible to non-employees. Now, the public can enter through the highly policed and surveilled gates of Building 77, which has a food court, and into the outdoor interior of the yard to access the ferry stop. However, the public is not allowed into any other part of the Brooklyn Navy yard asides from this access corridor.

Recently, there has been a focused effort to demilitarize the Brooklyn Navy Yard by evicting two tenants: Crye Precision and Easy Aerial, “which produce gear and technology for the Department of Defense, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Israeli Occupation Forces (officially known as the Israeli Defense Forces)” (Shepard, 2025). Many community members are shocked to learn that the BNY houses military contractors, since those businesses are labeled as “Fashion” and “Fine Art/Photography” respectively. Crye Precision manufactures tactical gear for warfare and Easy Aerial manufactures military drones. The reputation of the Brooklyn Navy Yard over the past few decades has evolved into being a tech hub for mission-driven, creative or sustainable entrepreneurs, and yet the presence and BNY’s protection of the two “open secret” military contractors is very much at odds with this vision.

Flooding Concerns Under Present Land Use

The current land use of the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a tech hub is one of the major reasons this low-lying coastal area is being targeted for better water management to mitigate coastal and pluvial flooding. Although there have been significant investments made to the Brooklyn Navy yard to update the infrastructure from it’s civil-war era construction, water pools quickly on the interior, non-public streets where sewers are unable to convey water (see site visit photos during a short cloudburst rainfall event), and water will flow downhill into the area, as it was originally a salt marsh fed by tributaries.

There remains lots of interesting research questions about how best to manage flooding in the BNY for the future. Many green and blue infrastructure projects use soil permeability as a tool for absorbing stormwater runoff, but this is a more complicated issue at the BNY. One, the coastal soil will already be saturated with salt water to a certain level, limiting absorption of surface stormwater. Additionally, US Army and Navy bases have not and are not subject to environmental rules the same way that other land within the US is, and given the heavy industrial history, uncapping soil in this area might have unintended consequences.

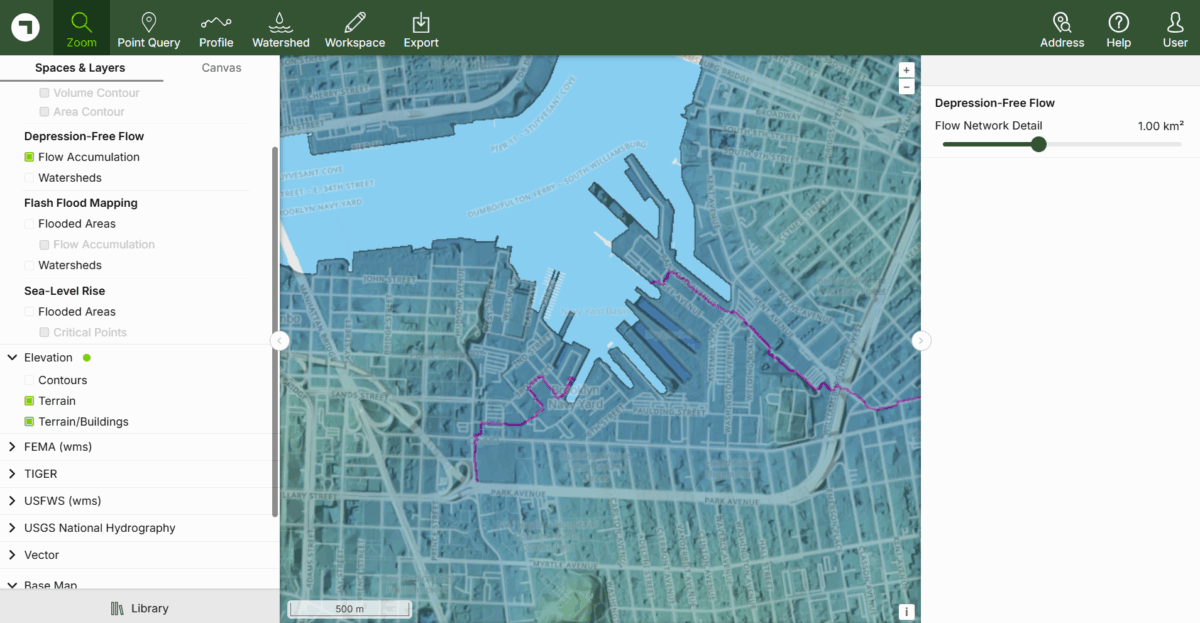

Despite a 300+ year history of development, stormwater flows roughly the same way into the BNY. One of the green companies at the BNY’s tech hub is Scalgo, which maps out flow patterns and flooding over topography. In the screenshot below, their own model shows the main contemporary tributaries (where the water flows over the impervious surface). These flow paths are similar to the streams seen in the Welikia map rendering (first figure), as well as the Wallabout Bay Map (second figure). By starting with a deeper contextual understanding of the hydrologic and social history of the site, our conceptual data monitoring dashboard can better facilitate and evaluate effective and regionally appropriate site specific interventions to mitigate flooding.

Today:

Site Visit: Brooklyn Navy Yard Flooding

Our team went on a site visit to the Brooklyn Navy Yard on June 19, 2025 to assess accessibility of the area, get an understanding of the various industrial businesses present, and composition of stakeholders and community members that live around the Brooklyn Navy Yard. During the duration of our trip, a cloud burst happened which brought 0.46 inches of rain in the overall general New York City area and over 0.29 inches for Brooklyn in less than an hour. The severe thunderstorms that lasted just a few minutes allowed us as a team to visualize how water flowed across the Brooklyn Navy Yard and areas which it pooled. It was later recorded by local news, there was damage to several areas around New York City with fallen trees on cars and other debris.

Stakeholders & Accessibility of the Brooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy yard has over 550 businesses and employs more than 11,000 people. The Navy Yard itself does not contain residential sites, however, immediately outside of the secured area there are residential buildings, private houses, and various other businesses. Public and private residential composition, along with demographic information can be found below:

- The Farragut Houses, managed by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA)

- Navy Green, a mixed-income development which supports housing for formerly houseless individuals, with affordable rentals, homeownership units, and retail

- Navy Yard Housing Cooperative, a private apartment community

Since the Brooklyn Navy Yard is a secured area, accessibility is challenging if one does not have the proper permissions to visit the site. However, even for those who have access and are employed there, there is a disconnect between people and the waterfront. The area was not designed to invite employees or visitors to enjoy the waterfront during breaks. Furthermore, lack of benches, shade, and hard infrastructure makes it an uninviting place. In general, access to the waterfront in New York City is not always equitable for various, especially marginalized communities. For community residents and stakeholders who live around the Brooklyn Navy Yard, even though the proximity to the waterfront is close, several challenges pose to get there.

Flooding Challenges

Severe thunderstorms and rainfall allowed us to witness the various issues that exist in the area. Walking across from one point to another was challenging due to the flooding from rainfall within a short amount of time. The Wegman’s Parking Lot was a case in point where people with shopping carts had to cross over to the street to avoid the flooding and be able get across. Although there was a design element to one corner of the parking lot, where water was able to flow out, it had a hard time keeping up with the surge of rainfall and took some time to drain the area.

Existing Resources

There are existing tools that can be implemented at the Brooklyn Navy Yard to measure and understand patterns of rainfall and flooding. The Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay has deployed censors throughout New York City to monitor flooding. FloodNet sensors capture real-time data on flooding, including the presence, frequency, and depth of localized street flooding events. The data is publicly accessible and displayed on a dashboard in real time.

Another valuable tool is the use of Sea Grant’s MyCoast app which allows community members and stakeholders to document flooding events. The use of these tools allows for more community agency and decision-making. Stakeholders are able to access the data and contribute to documenting flood events to help inform safety protocols and hold accountability for City management of these concerns.

Right: Sea Grant’s MyCoast app, credit: MyCoast NY

Green + Blue Roofs

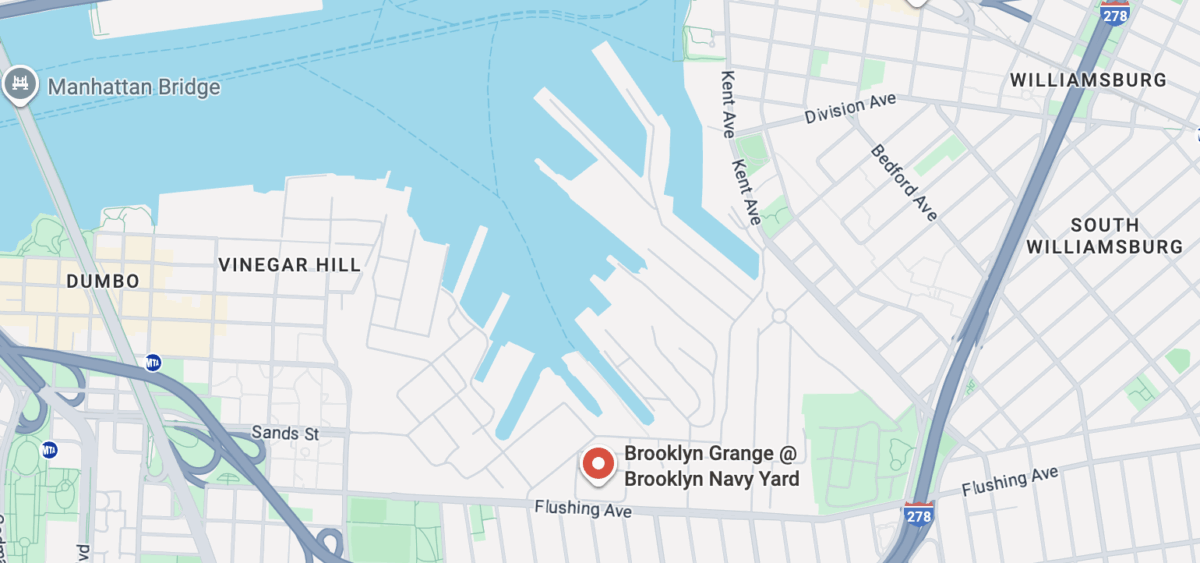

Our team also visited the Brooklyn Grange, a roof-top urban farm located within the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The rooftop has multiple functions from absorbing rainfall, creating pollinator habitats, to creating fresh and healthy, local produce. A building adjacent to Brooklyn Grange, also had a green roof with vegetation planted across. Design benefits of green roofs, help to retain stormwater while it is slowly released through evaporation and utilized by plants. Green roofs significantly reduce the amount of rainwater which would otherwise run off on impervious roof surfaces. Multiple functions make it easier to address heat island effect, lowering overall temperatures, encouraging native pollinators, and producing healthy vegetables. It should be a design strategy that is implemented across buildings not only in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but across New York City.

A Possible Tomorrow:

The Brooklyn Navy Yard still struggles with water management, and parts of it are projected to be underwater at future high tides due to sea level rise. How can we use our observations and existing knowledge to learn how to manage water? In other words, how can we take information from the dashboard and put solutions into action? Here, we’ve proposed a series of monitoring techniques and infrastructure updates on a specific site to ground-truth existing models and adapt the Brooklyn Navy Yard to live with water.

Case Study: The Wegman’s Parking Lot

We saw a lake and a waterfall form in the Wegman’s parking lot after a short, intense burst of rain on June 19th, 2025. As beautiful as this impromptu river and waterfall may be, we don’t think it belongs where people are walking, and we’re concerned at how quickly the sewer was overwhelmed. We asked ourselves two questions: how is this being modeled (i.e., was this a predictable flooding event?), and what can we do?

To answer the first question, we turned to SCALGO, a geographical digitization tool that can provide a visualization of water movement and flooding based on the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s topography. Here’s our site on the map:

Then we took a closer look:

Then, we checked to see if the flash flood model corroborated what we saw:

The blue pin on Sand Street is where we saw water accumulating and flowing into the sidewalk and street, and the upstream area (green) reflects the direction we saw water flowing in. After a short flow path (dark blue), it Interestingly, SCALGO also modeled flooded areas in the parking lot that we did not observe, including a flow path right though the Wegman’s building itself, which must be too new for the model to recognize, since it isn’t highlighted in yellow. We can work around that, which brings us to our next question – what can we do about the flooding? We broke this down into two more sections: monitoring for accuracy and managing water in the meantime.

Monitoring Proposal

Water can come from three places at the Brooklyn Navy Yard: precipitation, upstream, and the sea. For this site, we focused on precipitation and upstream. To measure water coming from the sky, we need a weather station, and the nearest weather station to the Brooklyn Navy Yard is located in Manhattan, on 13th and 16th (NYC Micronet, 2025). This is fairly useful, but precipitation events can be highly localized. The Brooklyn Navy Yard needs its own weather station to accurately measure the amount of precipitation it receives, and we propose putting it on top of building 77, where the Brooklyn Grange is currently located:

That takes care of on-site precipitation, now we need to deal with water coming from upstream. How much water is there, and how can we manage it? Let’s start with water movement, by inputting flow meters “upstream” and “downstream” our nature-based solution:

Nature-Based Solution Proposal:

On our site visit, we noticed that the Wegman’s parking lot contained beds for plants, but that these beds were raised, so water flowed around them instead of into them. Using a photo we took of the flooding, here’s a simplified sketch of how the site currently looks, with water following the yellow arrows:

Our potential re-design using nature-based solutions of the site lowers the beds, but does not significantly alter the infrastructure of the parking lot (which is raised). We focused on lowering the large bed by the sidewalk and filling it with native species, but lowering the beds that line the parking lot would create a hazard for cars. We knew we had to lower it to collect and convey water, so we created an alternating pattern of bricks and open spaces for water to flow through while keeping cars from accidentally rolling in. The whole bed will be slightly sloped to convey water down and around the parking lot, with water following the yellow arrows:

Finally, we got specific and added sensors. In addition to the flow sensors, we wanted people to be able to see the temperature, soil moisture, and salinity of the recessed bed by the sidewalk. Additionally, we decided to propose an additional Floodnet sensor at the site to see how much water it collects, as well as a temperature sensor for the pavement so people could see the difference in real time. A QR code will be placed at the site on the pole where the Floodnet sensor is mounted so pedestrians have immediate access to the data. add photos of sensors

References:

Brooklyn Grange. https://www.brooklyngrangefarm.com/. Accessed August 2025.

Brooklyn Navy Yard. https://www.brooklynnavyyard.org/mission/. Accessed August 2025.

Brooklyn Navy Yard, Brooklyn, NY Demographics: Population, Income, and More. https://www.point2homes.com/US/Neighborhood/NY/Brooklyn/Brooklyn-Navy-Yard-Demographics.html#income. Accessed September 2025.

FloodNet NYC. https://srijb.org/floodnet-nyc/.Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay. Accessed September 2025.

June 19, 2025 Weather History in Brooklyn. https://weatherspark.com/h/d/24502/2025/6/19/Historical-Weather-on-Thursday-June-19-2025-in-Brooklyn-New-York-United-States. Weather Spark. Accessed August 2025.

MyCoast. https://mycoast.org/ny. Sea Grant New York. Accessed September 2025.

Navy Green. https://bchands.org/navy-green/. Brooklyn Community Housing & Services. Accessed September 2025.

New York City Micronet. https://www.nysmesonet.org/networks/nyc. NYS Mesonet. Accessed August 2025.

Sanderson, Eric. Welikia Project. Accessed 2025. https://www.welikia.org/

Shepard, Sophie. Demilitarizing the Brooklyn Navy Yard, June 27, 2025. https://www.counterpunch.org/2025/06/27/demilitarizing-the-brooklyn-navy-yard/

Wallabout Bay and the farming community in 1766; [19??], Map Collection, B A-1766 (19–?).Fl; Brooklyn Historical Society. https://mapcollections.brooklynhistory.org/map/wallabout-bay-and-the-farming-community-in-1766/

White, Nelligan. Walt Whitman and Ingersoll Homes. Accessed July 2025. https://nelliganwhite.com/projects/ingersoll-homes/