From Scarcity to Stewardship: Community-Driven Water Intelligence for Rural India

Framing the problem: a governance challenge, not just an infrastructure gap

In rural India, water does not simply flow through pipes. It flows through trust, power, and daily survival. When a pump fails or a tank runs dry, the problem is not only mechanical. It is about who gets water, who doesn’t, and who gets left out of the conversation when things go wrong.

Many rural communities lack visibility into how much water is available, where it flows, or what breaks when it doesn’t arrive. Monitoring is infrequent or non-existent. Maintenance is reactive. And when failures occur, decision-making is often centralized or dominated by local elites, excluding women, lower-caste groups, and youth from participating meaningfully in water stewardship.

Despite progress through different government programs, many villages still face:

- Unreliable supply — frequent pump failures, leakages, and reactive maintenance.

- Opaque systems — little visibility into how much water is available or where it flows.

- Inequity — marginalized groups, women, and youth often underserved or excluded from decisions..

- Low ownership — centralized control and elite capture weaken accountability and trust.

- Weak incentives — few drivers for conservation or timely repair.

This is not just an infrastructure gap. It is a governance challenge — one that requires new ways of sharing information, distributing responsibility, and empowering communities to manage water fairly and sustainably.

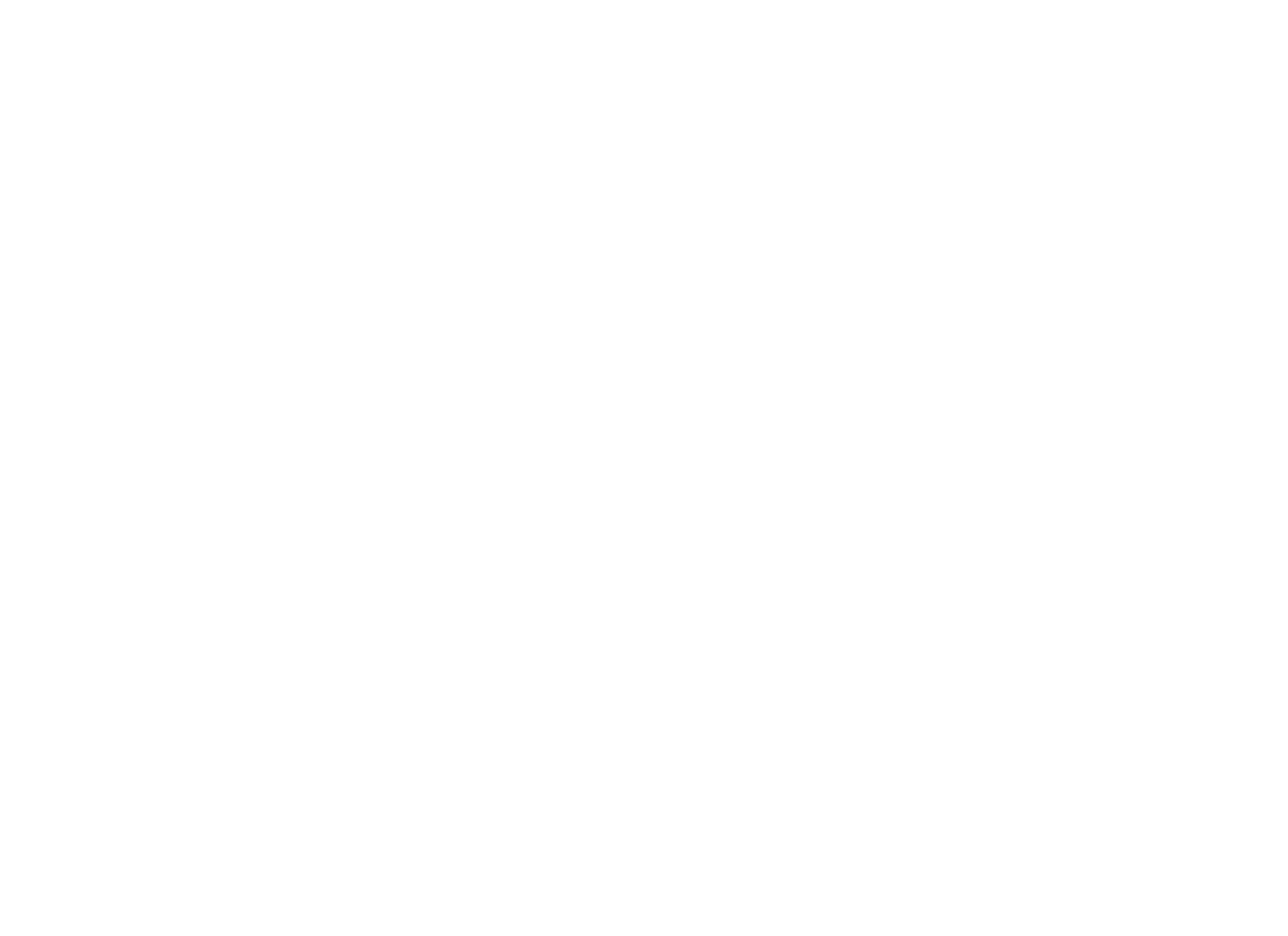

Recognizing this gap was the starting point for developing Jal Saathi: a community-driven, tech-enabled governance scaffold for rural water systems. Unlike a hardware intervention, Jal Saathi shifts how decisions are made, how information circulates, and how agency is distributed across the water ecosystem. Jal Saathi isn’t a product. It’s a toolkit for autonomy.

Value Proposition

“A modular, digitally-enabled model that empowers villages to monitor, manage, and sustain their own water, unlike traditional top-down schemes that often suffer from poor maintenance, low adoption, and lack of community buy-in.”

Jal Saathi is a community-driven, tech-enabled governance system that makes rural water reliable, fair, and transparent. By combining real-time data from low-cost sensors with public scorecards and inclusive village committees, Jal Saathi gives communities the tools to see where water flows, fix problems before they escalate, and ensure that no household is left out. Unlike traditional top-down schemes that break down over time, Jal Saathi turns infrastructure into stewardship—shifting power, visibility, and accountability back to the people who depend on water every day.

Vision

“To create a future where every rural village in India is a self-managed water community — where every household receives its fair share of clean water, and every citizen plays a role in protecting this shared resource. This vision is powered by digital tools, real-time data, and community-led governance that makes water systems fair, transparent, and sustainable.”

The Solution

Jal Saathi is not just another water solution or device. It is a community-driven governance toolkit that combines digital monitoring with transparent decision-making and behavioral incentives with the goal of rebuilding trust in rural water systems. In India, pumps and pipelines may break but their biggest failure is invisible: governance. Jal Saathi makes governance accountable, visible and fair.

The solution has three layers that intertwine with each other:

- IoT Monitoring: To make the invisible, visible. Low-cost sensors will be installed on pumps, tanks, and pipelines to track flow pressure, water turbidity and tank levels in real time. The devices are compatible with solar power and low-connectivity networks (LoRaWAN and GSM) and data will be visible and accessible to both the residents and the local officials.

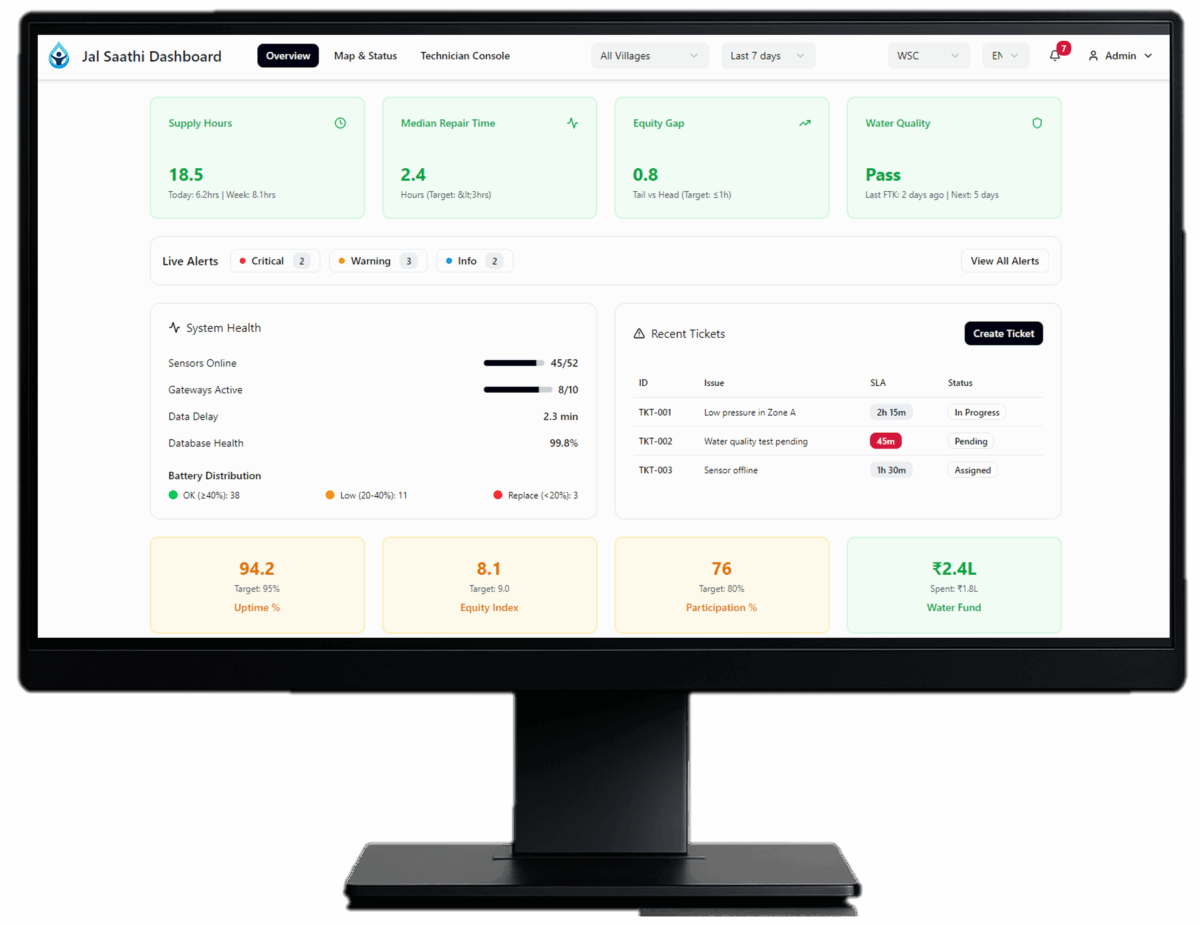

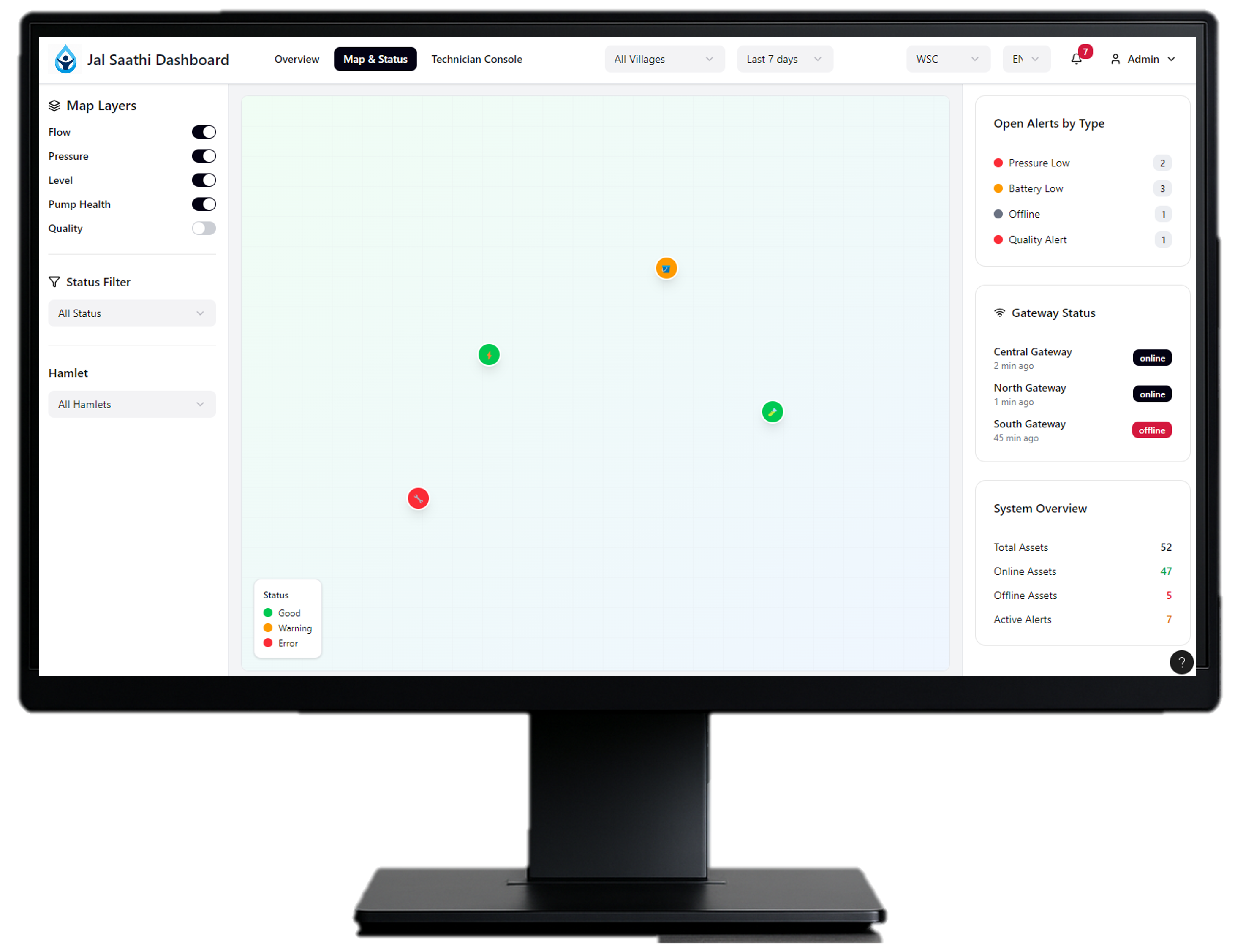

- Accessible Dashboards: Data must be translated into simple and visual scorecards. The scorecards will be like traffic lights for daily quotas, alerts and health. The scorecards will be shared via the community boards and can be accessed via an app for smartphone users.

- Governance Tools: A water stewardship committee (at least 50% women, youth, marginalized voices) will interpret data, coordinate repairs and present the monthly performance to the village assembly. Participation will be tracked through a water scorecard that covers equity, responsiveness, and inclusion.

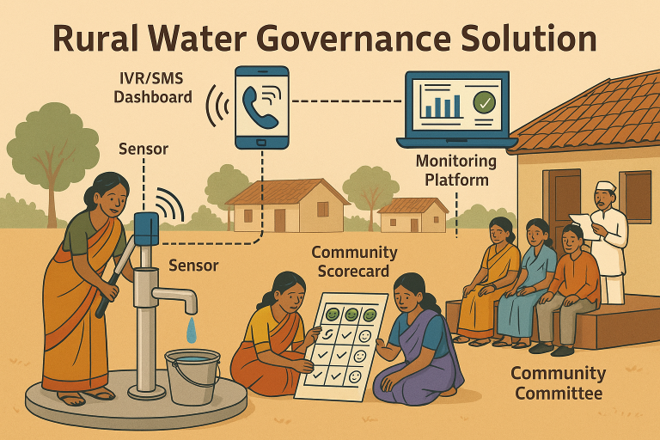

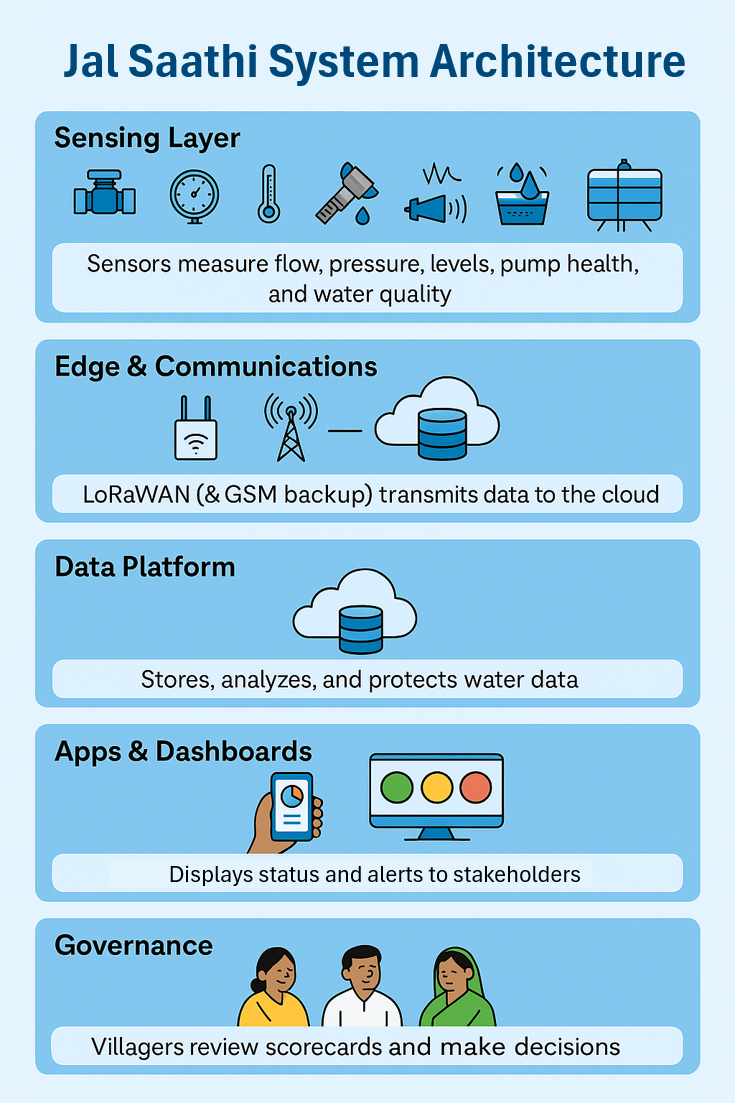

System Architecture: How It All Connects

Jal Saathi works like a digital nervous system for rural water. Each layer plays a role — from sensing problems in the pipes to helping villagers make fair decisions.

1 Sensing Layer – Smart Eyes & Ears

- What it does:

- Flow sensors on pipes measure how much water is moving.

- Pressure sensors check if water reaches everyone, even at the far end of the village.

- Tank level sensors show how full or empty storage tanks are.

- Pump health sensors (vibration/current) tell us if a pump has stopped working.

- Water quality probes test for clarity, pH, and dissolved solids.

- How it works: all these sensors are powered by small solar panels so they work even without electricity.

- Why it matters: These devices make invisible problems (like leaks or low pressure) visible in real time.

2 Edge & Communication – The Messenger

- What it does: delivers sensor data from the village to the cloud.

- How it works:

- Sensors send data wirelessly using LoRaWAN – Long Range Wide Area Network. It’s a low-power, wide-area networking (LPWAN) protocol designed specifically for IoT devices that need to transmit small packets of data (like water levels, pressure, or pump health) over long distances with minimal energy use.

- Data goes to a LoRaWAN gateway (a small antenna box placed on a school or Gram Panchayat office). The gateway is connected to the internet (via broadband or mobile data). It bundles all the sensor messages and sends them to the cloud.

- If LoRaWAN isn’t available, sensors can use a GSM as backup. – Global System for Mobile Communications. Even remote villages often have at least 2G signal, so GSM can work where internet or broadband doesn’t exist. Any low-cost sensor with a SIM card can use GSM to “phone home” with water data.

- Why it matters: Even in remote villages with weak connectivity, the system still delivers data reliably.

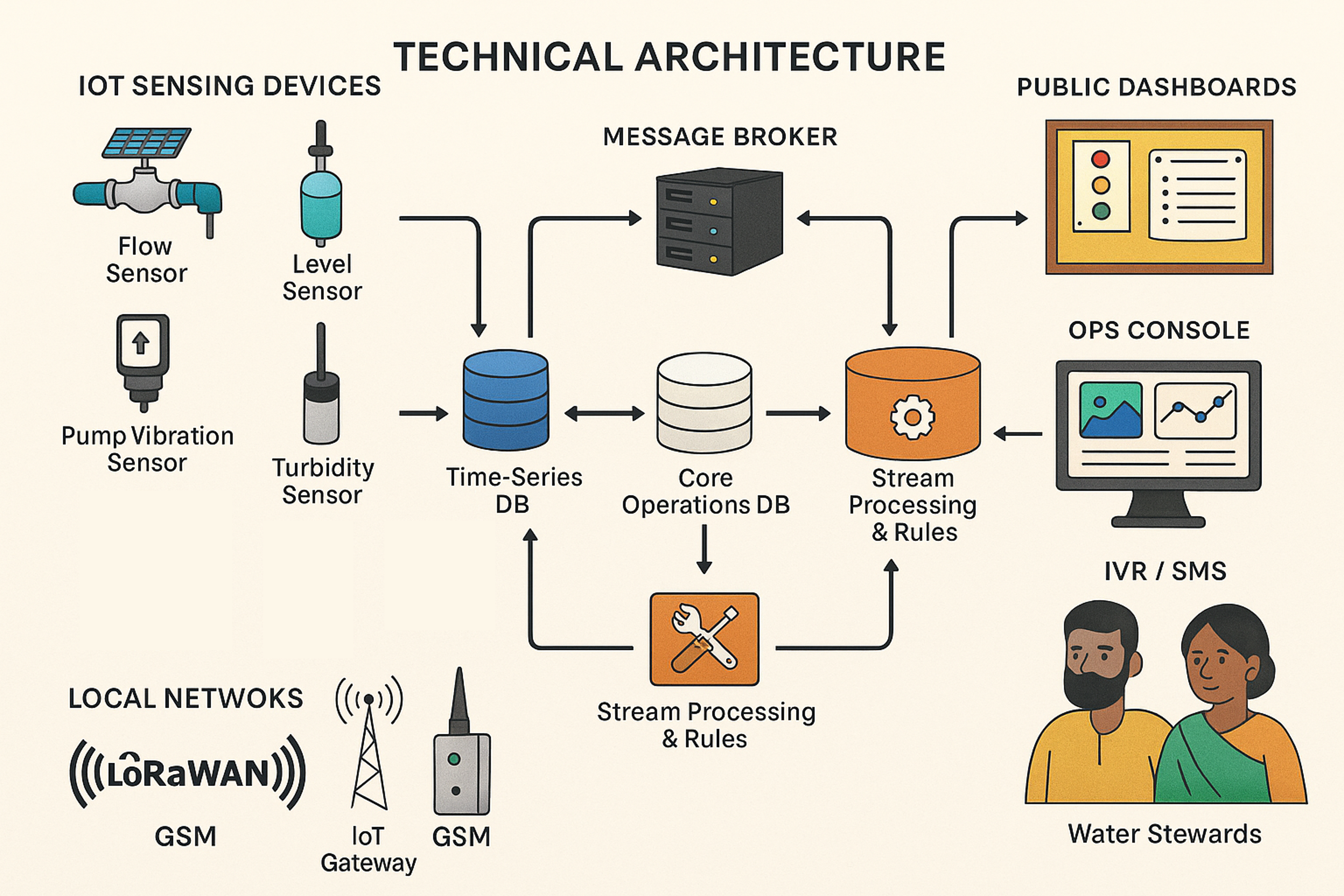

3 Ingestion Pipeline – The Organizer

- What it does: Collects all incoming data, authenticates devices, and organizes messages.

- How it works: Gateways send data to a secure server where it’s stored, cleaned, and checked for errors.

- Why it matters: Ensures only accurate, verified information flows into the system.

4 Data Platform – The “Brain” in the Cloud

- What it does: Stores, analyzes, and protects water data.

- How it works:

- A message broker receives sensor data and organizes it.

- A time-series database stores measurements like flow, pressure, and tank levels over time.

- Object storage holds photos and documents, like water test results or committee minutes.

- A rule engine checks for problems: e.g., if the pump hasn’t run in a specified amount of hours, or if the tank is almost empty.

- Why it matters: This layer turns raw numbers into useful insights and alerts. Villages and governments can see the full history of water performance — not just today’s numbers

5 Processing & Alerts – The Watchdog

- What is does: Turns raw data into useful actions.

- How it works: If a pump hasn’t run for 24 hours (as an example), or if a tank drops below 20% (as an example), the system creates an alert.

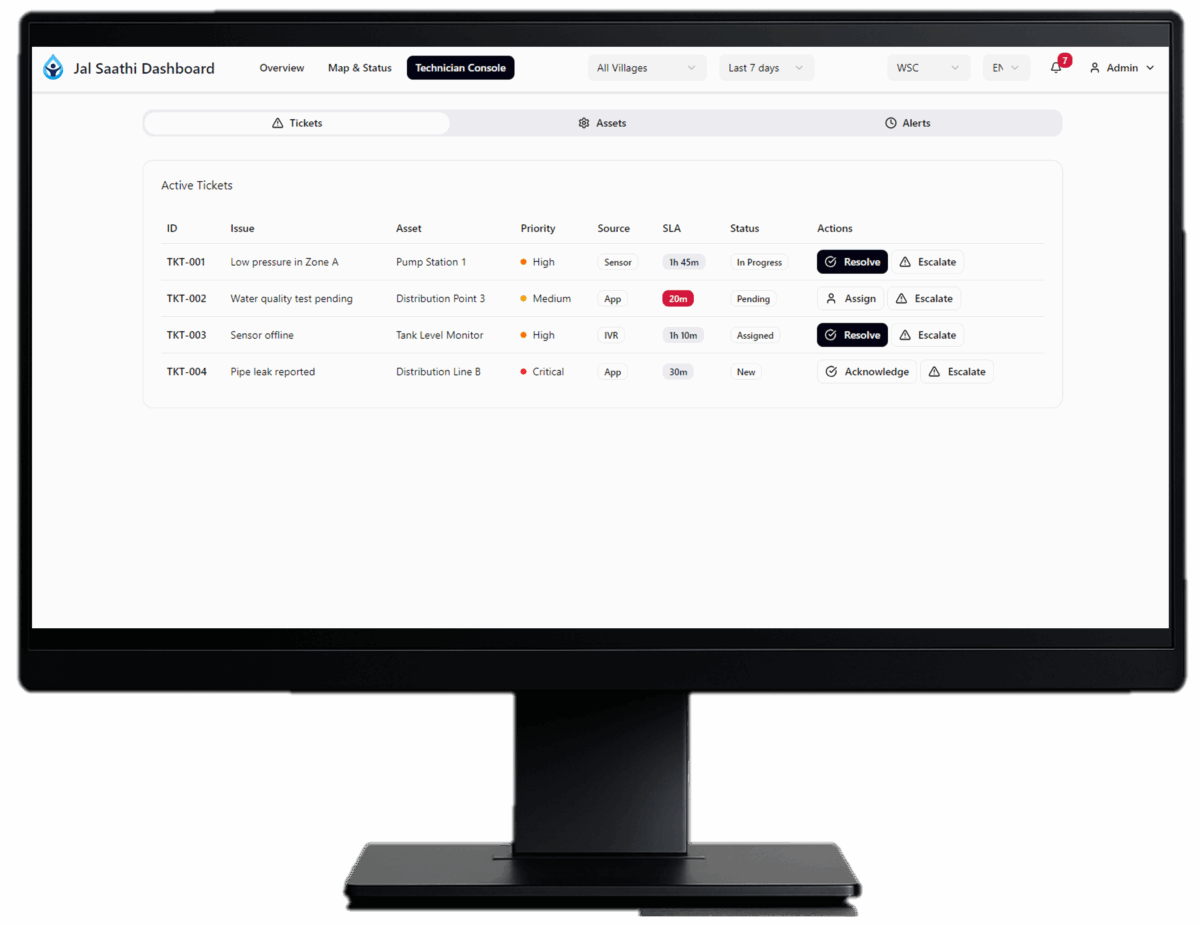

- Escalation: Alerts go first to the youth technician, then the Water Stewardship Committee, then up to the Panchayat and district engineer if not fixed within specified amount of time.

- Why it matters: Ensures accountability and quick fixes.

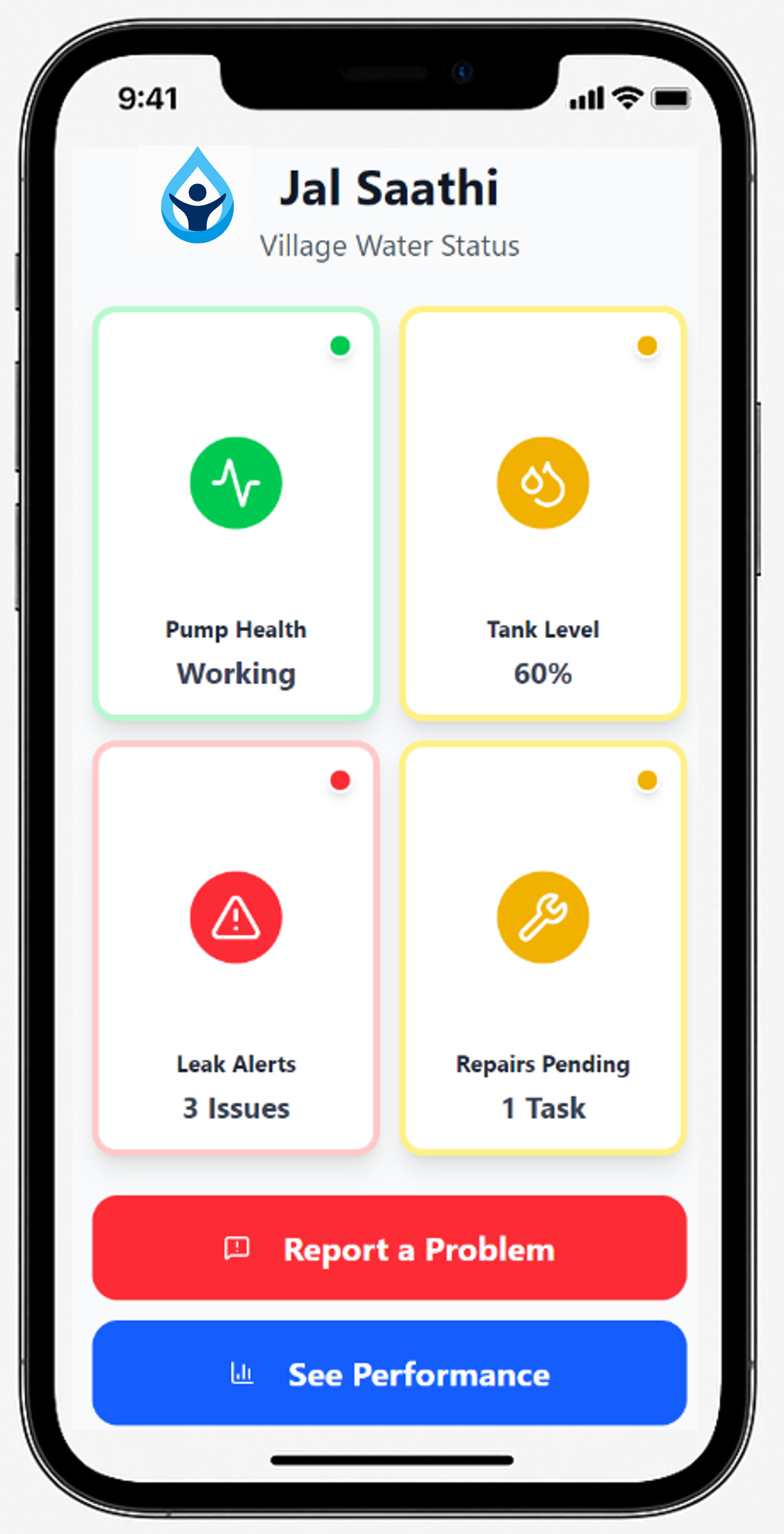

6 Applications & Dashboards – The “Windows” for People to See the Data

- Public Scorecards: Simple traffic-light posters (green, yellow, red) show supply hours, repairs, and fairness.

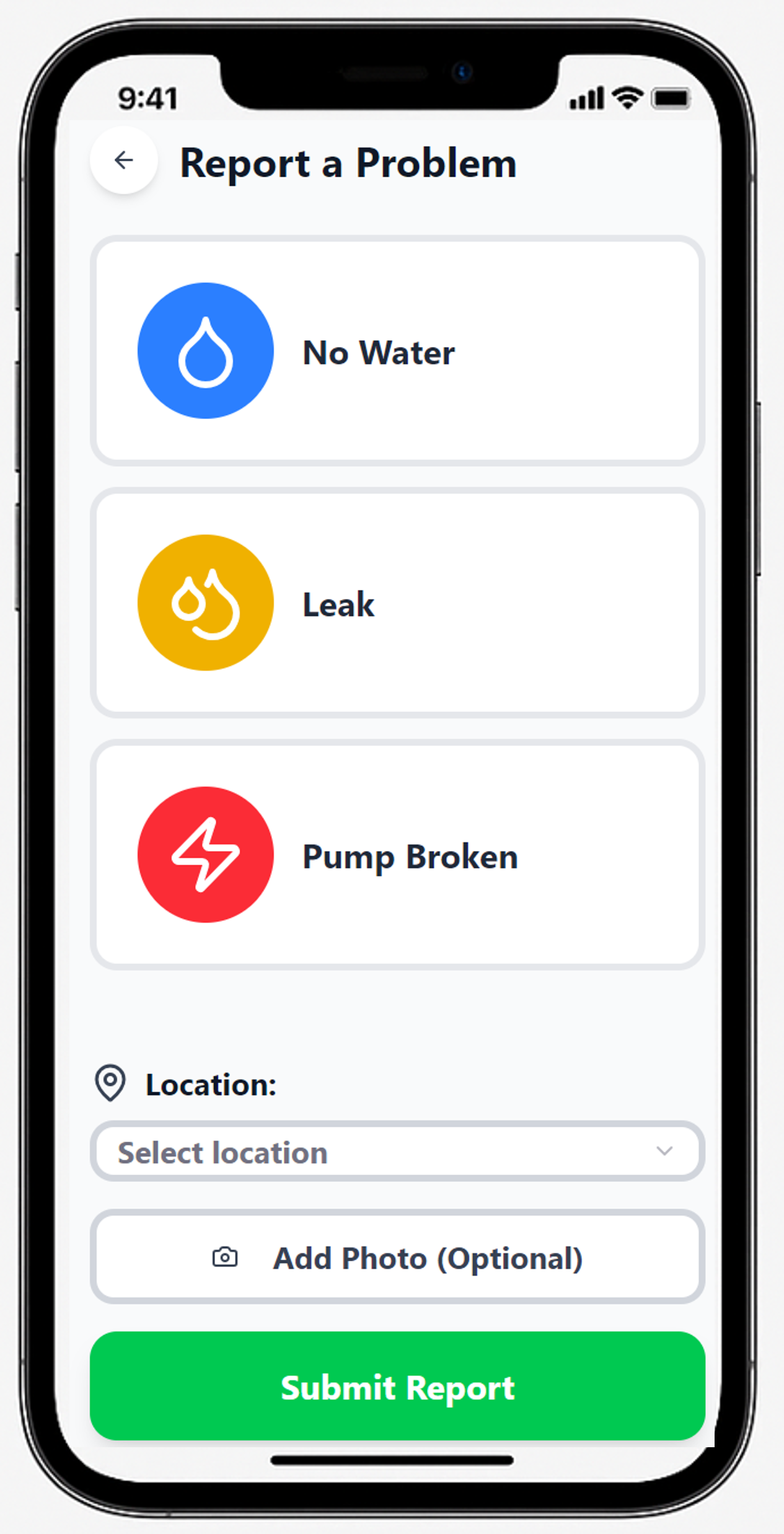

- Mobile App: Villagers and committee members can check live water status and report problems.

- IVR/SMS line: Anyone with a basic phone can call or text to report leaks or pump failures.

- IVR = Interactive Voice Response.

- It’s a phone system where you call a number and get a recorded menu: “Press 1 if the pump is broken, Press 2 if there’s a leak…”

- The caller presses a number, and the system records their problem automatically.

- SMS = Short Message Service, or simply text message.

- Villagers can send a quick text like “Leak at tank” or “No water today”.

- The system logs that message and creates a ticket for follow-up.

- IVR = Interactive Voice Response.

- Technician Console: Local youth technicians see status, alerts, and repair tickets.

- Incident workflow: ticket → triage → fix → verify (photo or sensor OK) → close with reason code.

- Government Dashboard: District officials can view data from many villages at once, linking directly to the Jal Jeevan Mission system.

- Why it matters: Everyone, from villagers to officials, gets the same clear picture of what’s happening.

7 Operations & Cost – Keeping It Running

- Spare parts & routine checks: Battery swap (12–18 mo), sensor clean (quarterly), calibration (6-mo), gateway health check (monthly).

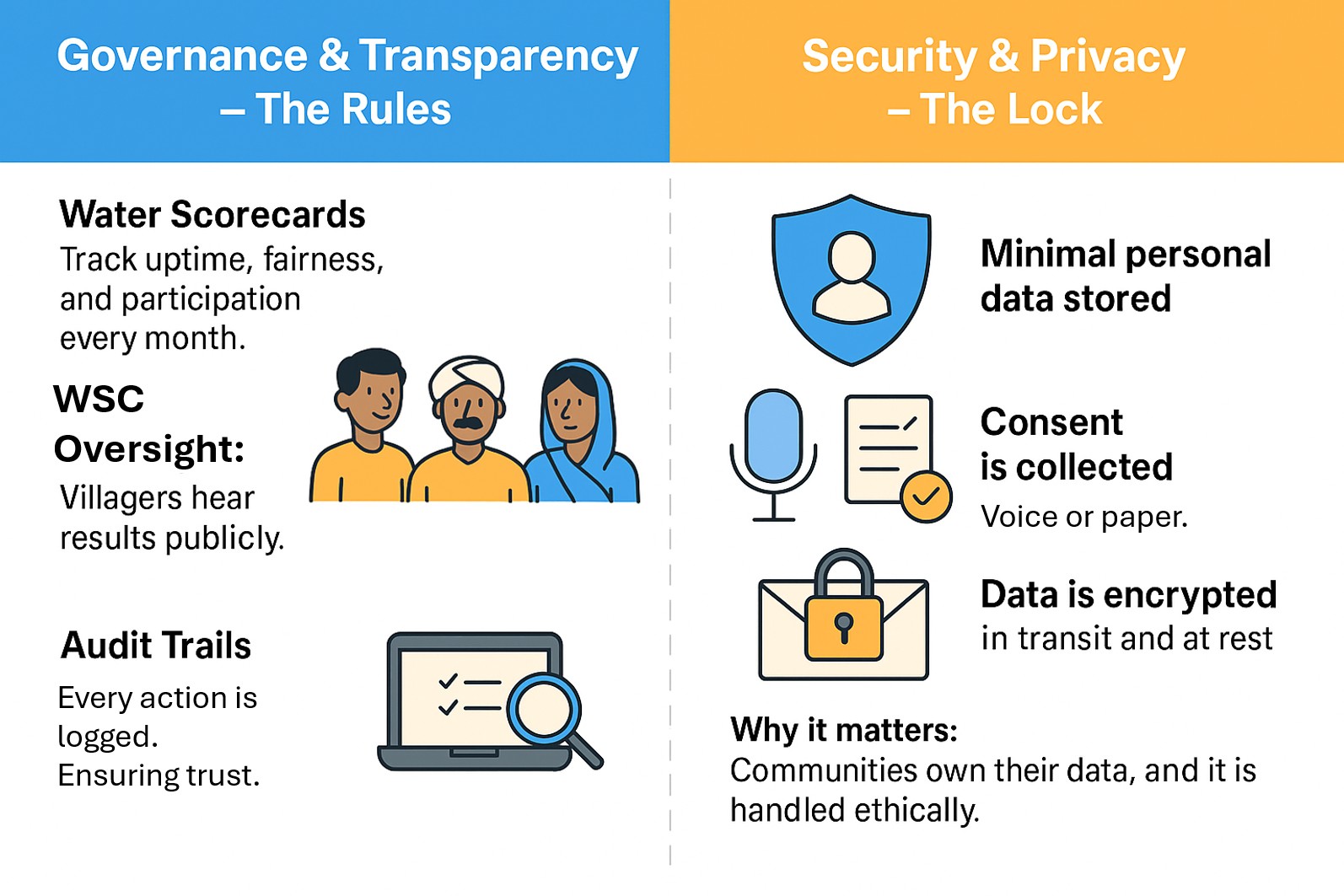

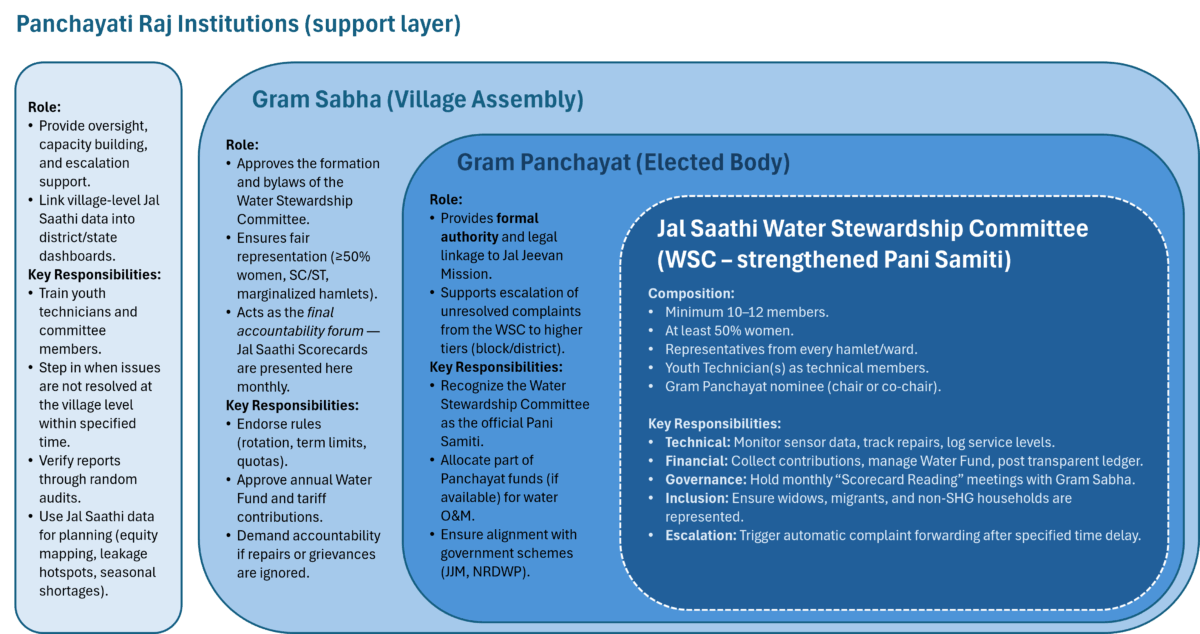

Governance

In rural India, water systems face challenges not only of infrastructure. But of accountability. Pumps breaks, leaks go unnoticed, and communities are left unsure of who should act. A governance model offers a way forward. It creates a simple roadmap that makes responsibilities visible, turning breakdowns into actions that can be tracked and solved.

This flow shows how governance turns problems into action. A leak becomes a “ticket” reviewed and resolved; scorecards make performance visible; and community meetings ensure every household has a voice. Instead of problems vanishing into silence, issues are tracked and fixed with transparency. By combining digital monitoring with collective decision making, this cycle turns fragile infrastructure into a service people can trust.

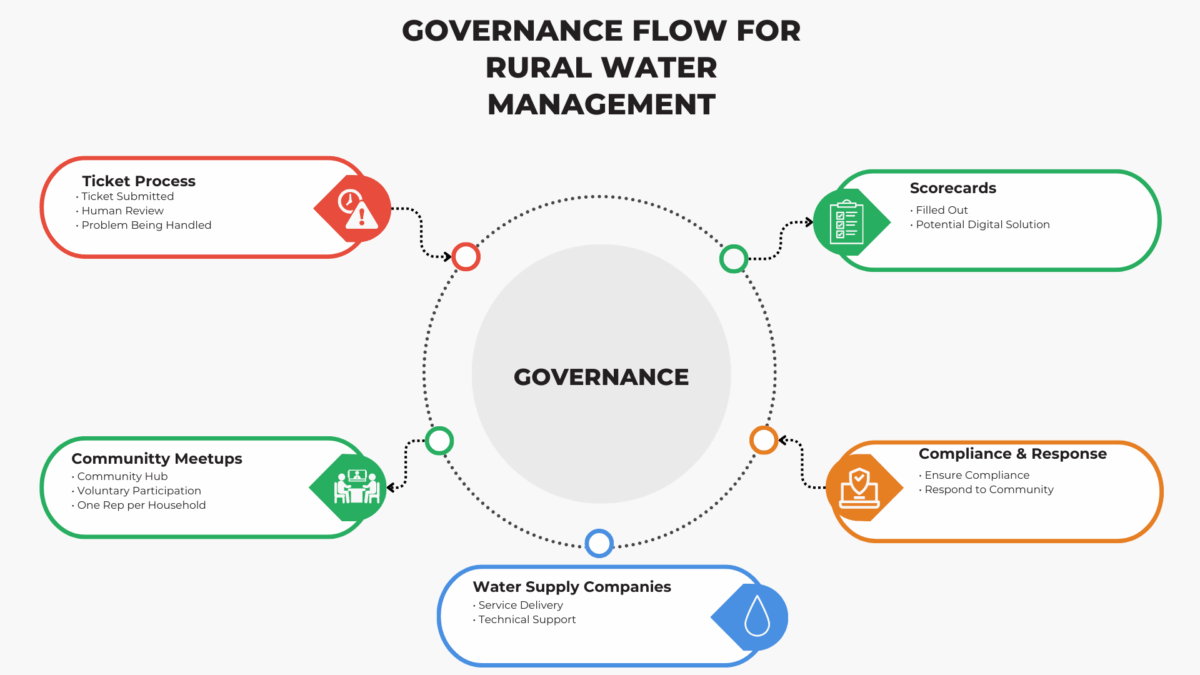

The stake holder value map, highlights who sustains this system. At the center, communities and their water committees gain real decision-making power. Around them, governments provide legitimacy, NGOs act as neutral supervisors, audits guarantee transparency, and SHGs strengthen women’s leadership. Technological partners add innovation, while saving funds give autonomy for small repairs. Together these roles create a balanced ecosystem where accountability is shared, and every actor benefits.

“The strength of this governance model lies in its ability to turn invisible gaps in rural water systems into visible, actionable steps”.

For Jal Saathi, this governance flow is the missing bridge between data and action. Sensors and dashboards on their own can measure water use, but they cannot guarantee fairness or repair a broken pump. By linking IoT alerts to community scorecards, meetings, and escalation chains, Jal Saathi turns information into accountability. It connects the village to Jal Jeevan Mission’s national systems, ensuring local voices feed directly into policy and planning. In doing so, Jal Saathi becomes more than technology—it becomes a platform for trust, equity, and shared responsibility in rural water stewardship

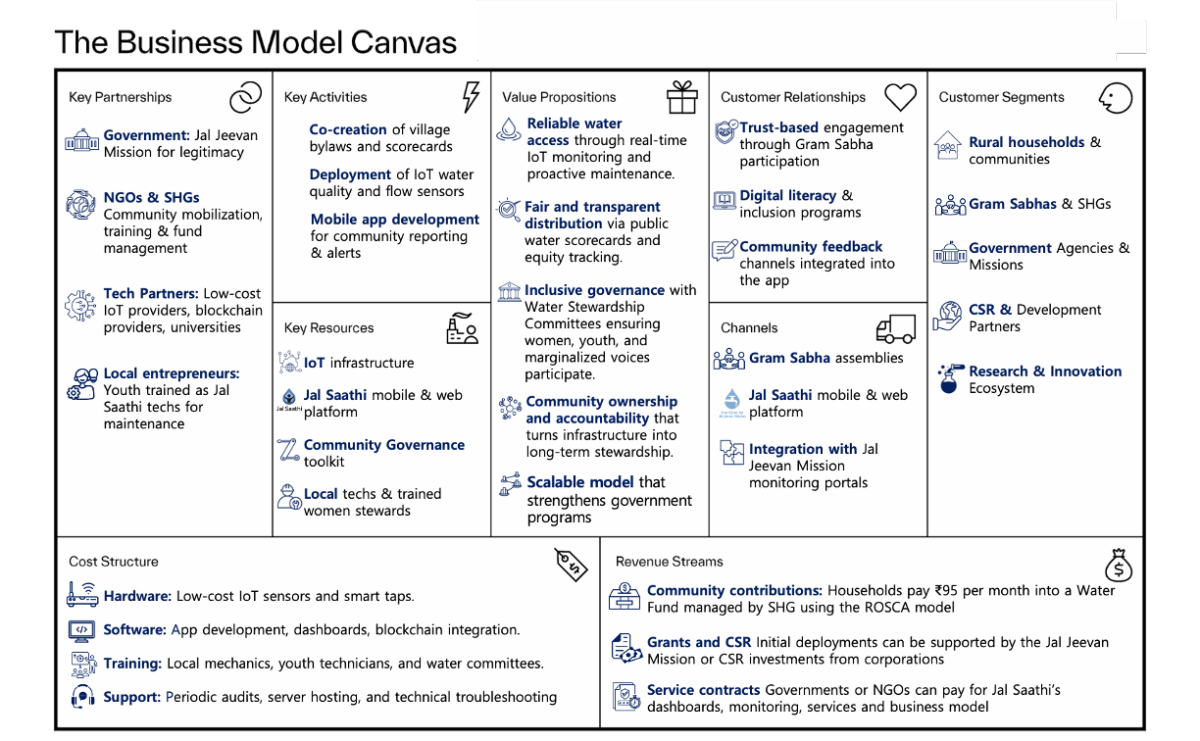

Business Model

Jal Saathi’s business model is modular, community-anchored, and government-aligned. It blends local contributions with institutional partnerships to ensure sustainability.

Value Proposition

- Reliable water access through real-time IoT monitoring and proactive maintenance.

- Fair and transparent distribution via public water scorecards and equity tracking.

- Inclusive governance with Water Stewardship Committees ensuring women, youth, and marginalized voices participate.

- Community ownership and accountability that turns infrastructure into long-term stewardship.

- Scalable model that strengthens government programs (e.g., Jal Jeevan Mission) with digital tools and local capacity.

Revenue Streams

- Community Contributions: Households pay ₹95 per month into a Water Fund, managed by Self-Help Groups using familiar ROSCA models (rotating savings) 2. Service Contracts: District governments or NGOs pay for Jal Saathi dashboards, monitoring, and reporting services.

- Tokenized Credits: Labor and in-kind contributions are logged on blockchain and can offset household payments.

- Grants and CSR: Initial deployments are supported by Jal Jeevan Mission funds or CSR investments from corporates.

To determine the tariffs we benchmarked the current water tariffs in India.

Current Rural Water Tariffs in India

- Under Swajaldhara / Swajal and WASMO, rural households typically contribute ₹30–100/month depending on the state and service model (sometimes higher in piped multi-village schemes).

- In Kerala’s Jalanidhi, community contributions for O&M are often ₹50–150/month per HH, depending on household income and water source.

Many Panchayats set flat tariffs:

- ₹30–50/month (handpump, basic supply).

- ₹100–200/month (piped household connections with better reliability).

Cost Structure

- Hardware: low-cost IoT sensors and smart taps.

- Software: app development, dashboards, blockchain integration.

- Training: local mechanics, youth technicians, and water committees.

- Support: periodic audits, server hosting, and technical troubleshooting.

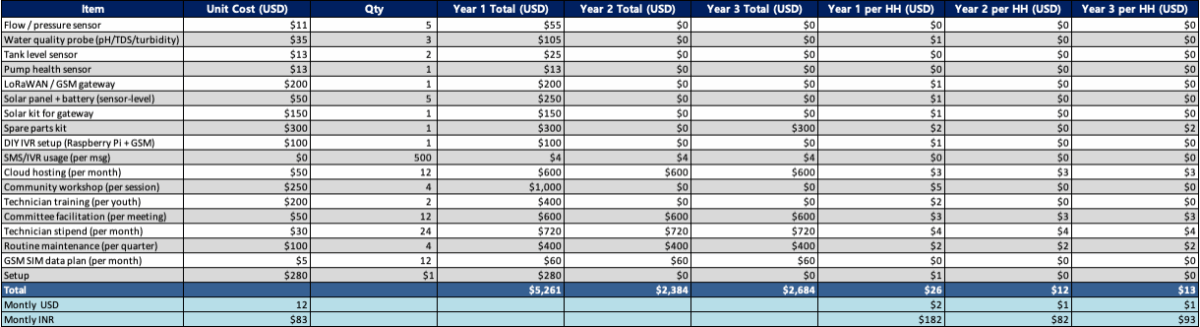

The following table shows the cost breakdown for the next three years as well as the cost per household.

The setup cost assumes that installation and calibration are carried out by local technicians trained under the Jal Jeevan Mission’s existing village-level cadres. This approach not only strengthens community ownership but also keeps deployment affordable.

If installation were conducted entirely by external technical teams or NGOs, travel, per diem, and coordination costs would increase substantially, raising total setup expenses by up to 65%

Key Partners

- Government: Jal Jeevan Mission for infrastructure and legitimacy.

- NGOs/SHGs: community mobilization, training, and fund management.

- Technological partners: low-cost IoT providers, blockchain developers.

- Local entrepreneurs: youth trained as Jal Saathi technicians for maintenance

Scalability

- The model is phased and modular

- Start with basic reporting and scorecards.

- Add IoT sensors as funding allows.

- Scale up with blockchain-enabled Water Funds and predictive analytics.

Target Group

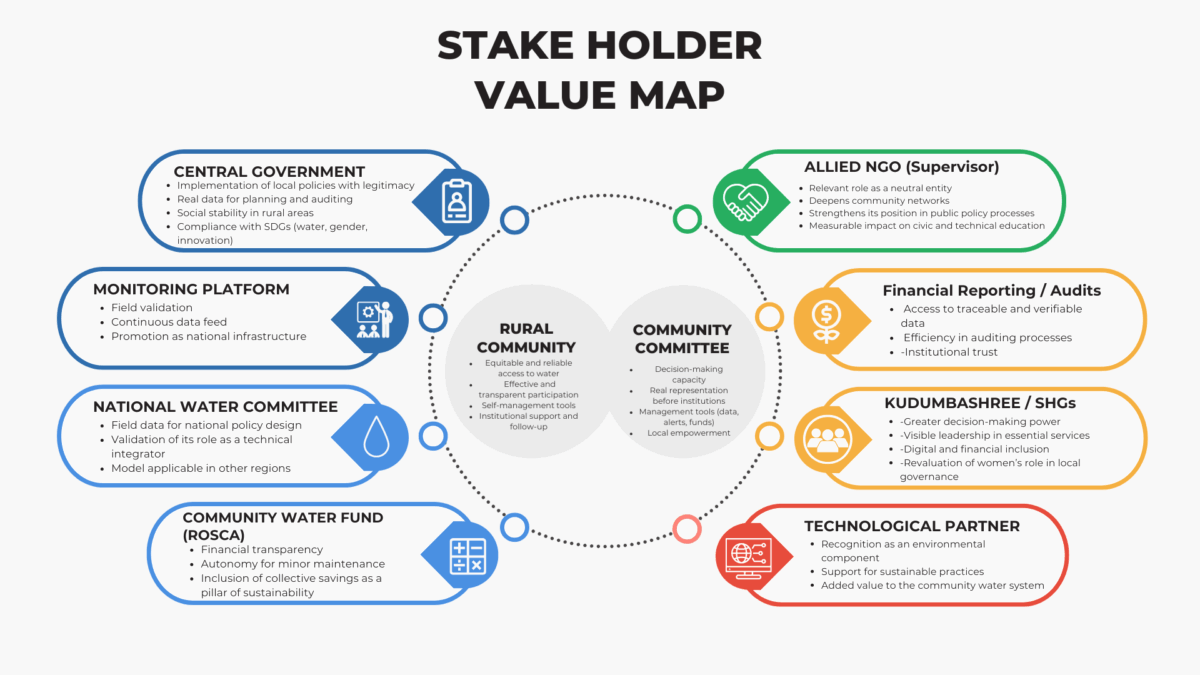

Jal Saathi is designed to work inside India’s existing governance fabric, not outside of it. That is why our primary target group is made of three interconnected layers:

- Government programs and subsidies – National initiatives like the Jal Jeevan mission provide the legitimacy, funding and policy support needed for scale. Jal Saathi feeds their dashboards with real time data, helping governments plan better, audit more effectively, and ensure that rural water schemes reach every household.

- Local water committees and panchayats – At the village level, institutions like the Gram Panchayat, Gram Sabha and Pani Samiti play a central role. Jal Saathi strengthens these bodies by giving them monitoring tools, transparent scorecards, and structured escalation chains. A strengthened water stewardship committee (WSC) becomes the daily operator, running systems, managing funds, assigning youth technicians, and reporting back to the Gram Sabha. This ensures that authority, accountability, and technical capacity remain rooted in the community.

- Rural citizens – Ultimately, Jal Saathi is built for the people most affected by inequity in water access. Women, migrants, and non-SHG households are given formal representation in committees, while all villagers benefit from transparent quotas, fair distribution, and faster repairs. By turning households into active participants through reporting tools, community meetings, and scorecards. Jal Saathi transforms users into stewards.

Beyond these three pillars, Jal Saathi also engages with supporting actors that reinforce sustainability.

- NGOs act as neutral facilitators, training communities and strengthening accountability.

- Self-Help Groups (SHGs) expand women’s leadership and connect water governance with financial inclusion.

- Technological partners ensure innovation and reliability of IoT systems.

- Finally, community water funds provide local autonomy for small repairs, reducing dependence on external aid. Together these groups create a governance ecosystem where national policy connects with local action, and local voices shape planning.

“Jal Saathi’s target it not just one actor, but the bridge between them all“.

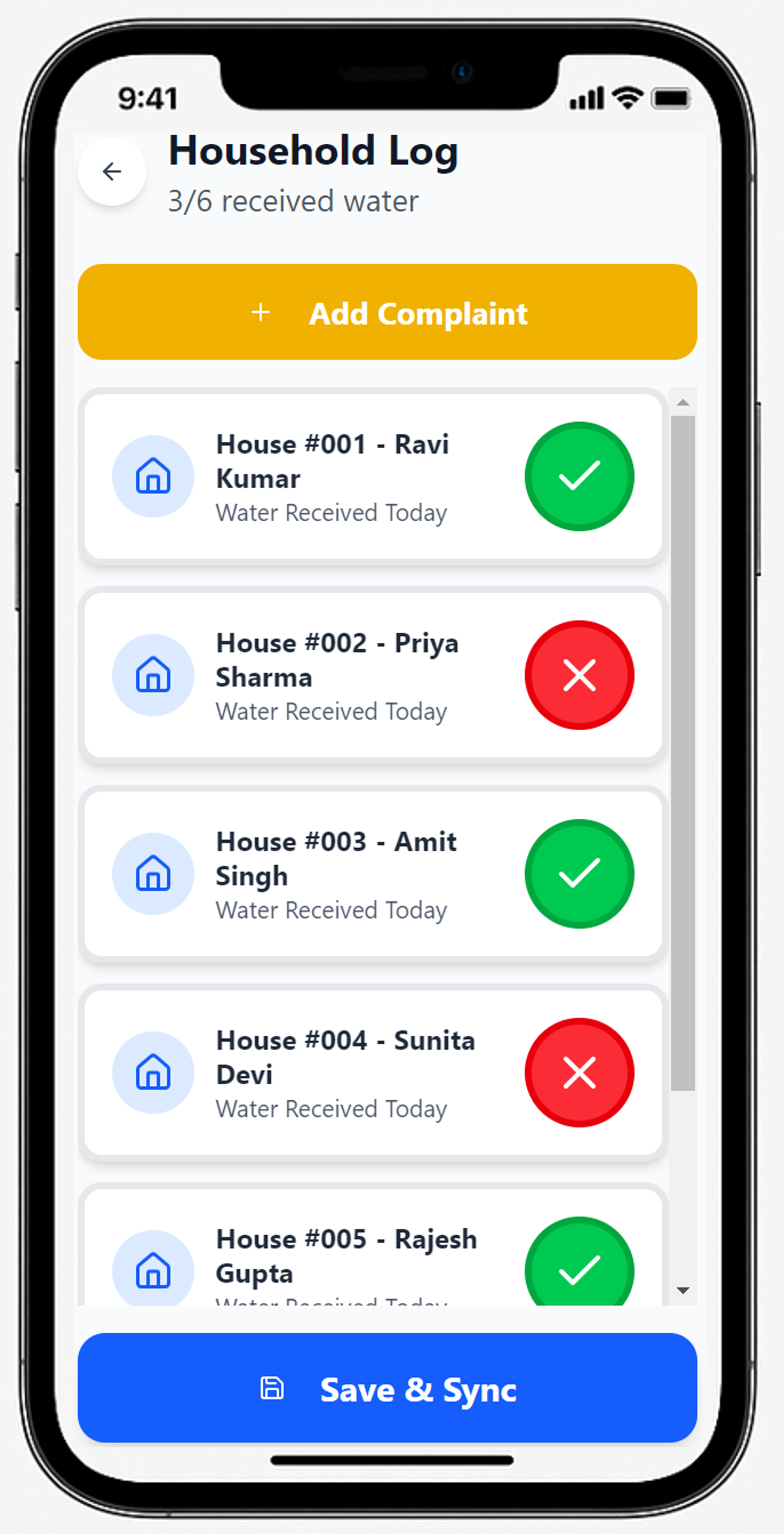

Prototype – App and Dashboard

Road map

Phase 1: Community Readiness & Governance Setup (Months 0-3)

The journey starts not with sensors, but with people. Partner NGOs mobilize the community and help establish clear bylaws in open Gram Sabhas: term limits, quotas (≥50% women, marginalized hamlets), and rotating roles to prevent elite capture. Key positions Tap Steward, Pump Monitor, Data Translator are assigned through transparent selection or public lottery. A universal household roster is created to ensure migrants, widows, and tribal families are not left out. Monthly “Scorecard Readings” begin even before hardware arrives, using simple posters and IVR lines to test governance dynamics first.

Phase 2: Infrastructure Installation & Onboarding (Months 3-6)

Once trust is established, the hardware follows. Smart flow meters and pump sensors are installed, and 2–3 youth are trained as certified Jal Saathi Technicians. Paid through the village Water Fund (a ROSCA-style savings pool), they handle calibration, battery swaps, and minor repairs. Each village keeps a spares kit sensors, batteries, fittings for quick fixes. This phase ensures that technology is embedded in local capacity, not imported as a black box.

Phase 3: System Integration & Mobile Engagement (Months 6-12)

The Jal Saathi app, IVR, and SMS channels go live, tested in local dialects for clarity and ease of use. Households are registered with smart IDs, and data flows into community dashboards. Tickets are logged automatically, escalated if unresolved for 24 hours (technician → committee → district engineer), and visible to all. Public scorecards display equity, repair times, and participation diversity. A grievance line bypasses committees to prevent capture, and “Data Translators” rotate monthly to explain dashboards in plain language.

Phase 4: Behavior Change & Gamified Engagement (Months 12-18)

With systems running, the focus shifts to culture. A “Water Equity Challenge” recognizes villages with the fairest distribution and fastest repairs. Leaderboards appear on kiosks, and small rewards or public recognition celebrate stewardship. Monthly meetings include Water Story Circles where elders and youth connect lived experience with data. Youth-led repair competitions, festival-linked conservation drives, and visible commitments (like “Tank cleaned by the 15th”) turn governance into a community ritual.

Phase 5: Monitoring, Feedback & Scaling (Months 18-26) – In Scope

Finally, Jal Saathi matures into a system of shared accountability. Quarterly audits sometimes cross-village validate scorecards against sensor data. Dashboards link to Jal Jeevan Mission platforms, producing anonymized insights for governments, NGOs, and utilities (always under community consent). Greywater monitoring modules extend the loop tap-to-source, enabling reuse for irrigation or recharge. Predictive maintenance and SDG-linked targets (e.g., repair time <48h, ≥50% women’s participation, ≥90% household coverage.) make progress measurable. Scaling is powered by a mix of community contributions, CSR grants, and district contracts ensuring Jal Saathi grows without losing its roots in local ownership

Phase 6: Intelligent Transparency: Blockchain & ML (Months 26-32) – In Scope

At full maturity, trust is institutionalized through technology. Blockchain secures every transaction: who repaired, who paid, who benefited. The goal is to create tamper-proof, auditable records of service delivery. Machine learning models analyze water flow, sensor anomalies, and maintenance logs to predict failures before they occur, shifting the system from reactive repair to proactive prevention

By the end of this phase, the blockchain ledger operates in three pilot clusters, ensuring ≥90% data integrity, while predictive algorithms achieve 80% accuracy in forecasting pump breakdowns, reducing downtime by 30%. Technology, once a tool, now becomes a guardian of trust.

What Success Looks Like

By Month 36, Jal Saathi stands as a scalable blueprint for digital water governance that is able to combine community agency with intelligent systems.

Key Impact Metrics:

- ≥90% household coverage with functioning water supply.

- ≥50% women in decision-making roles.

- Repair time reduced to <48 hours sustained.

- 25% of greywater reused for local agriculture.

- 100% maintenance costs financed locally.

More importantly, Jal Saathi demonstrates that sustainability doesn’t emerge from hardware alone—it emerges from systems of trust strengthened by transparent data and local capacity.

Why this model works

This model is feasible because it builds on proven global precedents that combine technology, community ownership, and accountability. In Spain, Smart Water Management systems showed how real-time monitoring and demand-side policies can reduce waste and improve equity without always expanding infrastructure (IDDRI, 2020). In Ireland, Group Water Schemes demonstrated that when communities are both users and managers, with cooperative governance and transparent tariffs, services become more reliable and inclusive (Alliance of Community-Owned Water Services, 2021). Urban governance in Shamsabad, Pakistan, confirmed that local committees with institutional oversight and external audits can safeguard participation and prevent elite capture. Sri Lanka’s community-based water management schemes proved that rural committees can run pumping, storage, and distribution systems sustainably when women and marginalized groups are included. Similar lessons come from Latin America, where Guatemala’s Agua del Pueblo showed that participatory planning, local tariff-setting, and training can sustain over 500 rural systems, and from Pakistan’s WASEP program, which reduced waterborne disease by 25 percent through community-designed schemes. Even regional initiatives like CRIDF in Southern Africa highlight that resilience depends as much on governance flexibility as on infrastructure.

By blending these lessons with India’s Jal Jeevan Mission framework, Jal Saathi avoids inventing new structures. Instead, it strengthens existing ones with digital tools, inclusive committees, and transparent scorecards, making the model not only technically sound but also socially legitimate, affordable, and scalable within India’s policy and tariff realities.

International & Regional References

- Smart Water Management, Spain – Sensor-based flow monitoring, telemetry, and demand-side pricing improved efficiency in water-scarce regions. https://www.iddri.org/en/publications-and-events/blog-post/smart-water-management-europe-lessons-spain-frugality-adaptation

- Community-Owned Water Schemes, Ireland (ACOWAS-EU) – Group Water Schemes run as cooperatives where users are also managers, ensuring democratic governance and tailored rural tariffs. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/13/22/3181

- Urban Community Governance, Shamsabad (Pakistan) – Local committees with representation quotas and external audits manage water supply under institutional oversight. https://ecologyandsociety.org/vol30/iss2/art18/

- Community-Based Water Management, Sri Lanka – Rural committees handle pumping, storage, tariffs, and gender-inclusive governance for sustainable supply. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/14/5/762

- GoAL-WaterS (Cambodia, Laos, Jordan, Bosnia & Herzegovina) – UNDP–SIWI program strengthening water governance via inclusive decision-making, accountability, and policy reforms. https://siwi.org/goal-waters/?utm_source

- OECD Water Governance Initiative – 12 Principles (2015) provide a global benchmark on effectiveness, efficiency, and trust, used by countries like Mexico and the Netherlands. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/water-governance/the-oecd-principles-on-water-governance-and-implementation-strategy.html?utm_source

Indian Success Cases

- Jalanidhi Rural Drinking Water and Sanitation Project in Kerala – Introduced reforms based on demand responsiveness, community ownership, and cost recovery, ensuring villagers had a direct stake in their water systems. By empowering communities to plan, manage, and finance piped water schemes through user fees, it strengthened both sustainability and accountability. Over two phases (2000–2019), Jalanidhi implemented 5,884 schemes across 227 Gram Panchayats, reaching more than 452,000 households.

- Water and Sanitation Management Organization (WASMO) – Launched in Gujarat in 2002, pioneered community-owned and managed water systems to ensure safe and sustainable supply. Its success showed how government can act as a facilitator while communities take charge of planning, operation, and maintenance, with 224 water supply schemes built between 2004–2010 under this model.

SDG Alignment

This project directly supports the following Sustainable Development Goals:

-SDG 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation: safe and equitable distribution at household level.

– SDG 5 – Gender Equality: empowering women in water governance.

– SDG 9 – Industry, Innovation, Infrastructure: low-cost, modular IoT infrastructure.

– SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities: participatory local governance.

– SDG 13 – Climate Action: promotes responsible resource use and early warning for failures.

Meet the team

Belina Campos

Mechatronics Engineer with seven years of experience in the automation industry, currently working as a Technical Project Manager for an EV Company.

Carlos Oseguera

Background in Music Production and creative businesses, currently focused on metadata for Streaming platforms and TV.

Andrea Gomez

Background in Finance and eight years of experience in the appliance industry, currently focused on new business development.